January 11th, 2025

A Beginner’s Education in the History, Natural History, and Landscape Design History of Central Park: Part Six

“Mrs. B., Mrs. B.,” the friendly man whose name – Eugene Kinkead I knew as that of longtime writer and editor on the staff of The New Yorker, would call out cheerily as he opened the door to my Central Park Task Force office on the ground floor of the Arsenal. Such courtesy salutations from him were frequent in the early 1970s when he was spending a great deal of time writing A Concrete Look at Nature: Central Park (and other) glimpses (Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., 1974). Re-reading it now, I see that the chapter on “Central Park Squirrels” provides an answer to the question of why these fascinating acrobatic creatures are seen mostly in proximity to the park’s entrances. Relaying to the reader facts from the tutorial he had derived from the American Museum of Natural History’s eminent mammalogist Dr. Richard G. Van Gelder, Kinkead writes:

“In Central Park, entrances are locations that have a distinct squirrel value. The animals get most of their food from human handouts. Thus they are directly dependent on the volume of human traffic.

As far as the name of this mammalian species is concerned, it appears that “squirrel” is initially derived from the Greek skiourous (formed of the roots skia, shade, and oura, tail), the translation of which is “he who sits in the shadow of his tail.” The description, bestowed more than 2,000 years ago, especially fits the eastern gray (the type that inhabits Central Park). Of all the quadrupeds inhabiting eastern North America, none has a tail so splendid, dramatic, and useful. The nine-inch plume is roughly half the body length of the adult. Much time is spent fluffing and grooming it, an indication of its importance, the owner being particularly careful to comb out bits of foreign matter. One of the unhappiest squirrels I ever saw was sitting on a low limb of a tree near Summit Rock, the Park’s highest point just in from Central Park West at Eighty-third Street, trying with claws and teeth to remove some chewing gum that had become embedded in its tail.”

_

As you can tell from the titles of several of his books, my friend Roger Pasquier, is my go-to guru when I want to know anything about birds – both migratory and resident – that have caught my attention in Central Park. To read his excellent essay on this subject titled “An Oasis for Birds,” you are still able buy on Amazon a copy of the of The Central Park Book that I published, edited, and wrote in part in 1977 under the imprint of The Central Park Task Force.

As you can tell from the titles of several of his books, my friend Roger Pasquier, is my go-to guru when I want to know anything about birds – both migratory and resident – that have caught my attention in Central Park. To read his excellent essay on this subject titled “An Oasis for Birds,” you are still able buy on Amazon a copy of the of The Central Park Book that I published, edited, and wrote in part in 1977 under the imprint of The Central Park Task Force.

In the same category as Eugene Kinkead and Roger Pasquier in terms of graceful writing in the service of deeply researched natural history, Marie Winn has achieved recognition for the literary results of her passionate avocation of persistently observing Central Park’s wildlife. Today she is best known in this regard for her captivating Redtails in Love: Pale Male’s Story (Penguin-Random House, March 30, 1999), with an Amazon blurb that reads:

At the outset of our journey we meet the Regulars, a small band of nature lovers who devote themselves to the park and its wildlife. As they watch Pale Male, a remarkable young red-tailed hawk, woo and win his first mate, they are soon transformed into addicted hawk-watchers. From a bench at the park’s model-boat pond they observe the hawks building a nest in an astonishing spot–a high ledge of a Fifth Avenue building three floors above Mary Tyler Moore’s apartment and across the street from Woody Allen’s. The drama of the Fifth Avenue hawks – hunting, courting, mating, and striving against great odds to raise a family in their unprecedented nest site – is alternately hilarious and heartbreaking. Red-Tails in Love will delight and inspire readers for years to come.

As they say, “That’s a hard act to follow,” but Winn did just that in Central Park in the Dark (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2008). Not surprisingly, this book about creatures that are likely to spend their lives as part- or full-time habitués of Central Park and its environs, is the story of her nocturnal meetings there with the group of compatible nature-oriented “regulars,” some of whom are those with whom she forged fast friendships during the nest-monitoring Pale Male era. It is therefore not surprising that in Central Park in the Dark she has a cast of regulars as faithful companions on her fearless night adventures that, according to the book’s dust jacket, “are played out around Central Park’s lakes and in its woodlands as night falls and then again in the gray hours before the sun rises, when nothing is quite as you might imagine it.

As they say, “That’s a hard act to follow,” but Winn did just that in Central Park in the Dark (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2008). Not surprisingly, this book about creatures that are likely to spend their lives as part- or full-time habitués of Central Park and its environs, is the story of her nocturnal meetings there with the group of compatible nature-oriented “regulars,” some of whom are those with whom she forged fast friendships during the nest-monitoring Pale Male era. It is therefore not surprising that in Central Park in the Dark she has a cast of regulars as faithful companions on her fearless night adventures that, according to the book’s dust jacket, “are played out around Central Park’s lakes and in its woodlands as night falls and then again in the gray hours before the sun rises, when nothing is quite as you might imagine it.

This rich assortment of sleeping birds, raccoons, bats, crickets, and fantastical moths featured as well as many unexpected amazements, like the discovery of slugs in acts that appear as a poetical form of randiness. But it is no surprise that owls are the stars in this mysterious dusky drama – not only thirty-eight screech owls that were introduced into the park some years ago, but also owl “tourists” and regulars that surprise experts and confound the local residents.

The reader soon finds that Marie is a conscientious writer who does her research with zest, a boon that the publicity description on the dust jacket calls attention to with its remark that an “eye-opening amount of natural history is packed into this entertaining book – on bird physiology, taxonomy, spiders, sunsets, moths, and butterflies, skimmers, meteor showers, the scientific purpose of curiosity, and the nature of darkness.” But the human drama is never forgotten: Central Park’s floating population of Night People young and old, as eager as Winn is to unlock the secrets of urban nature, are drawn into a peculiar kind of intimacy while they explore together the astonishing variety of wildlife in an urban park.

_

Propped up in bed last night as I finished reading Winn’s Central Park in the Dark, I looked out of the window at the nocturnal view of the southern half of Central Park and the northern third of mid-Manhattan with the brightly illuminated Art Deco Chrysler Building almost eclipsed by several still-under-construction apartment and office buildings known as “super talls.” Before turning out the light, I noticed on my bedside table The Falconer (Karz-Cohl, 1984) by Donald Knowler a British journalist and avid birdwatcher who set himself the challenge of listing all of the birds that he identified on regular walks in Central Park during a single calendar year.

Propped up in bed last night as I finished reading Winn’s Central Park in the Dark, I looked out of the window at the nocturnal view of the southern half of Central Park and the northern third of mid-Manhattan with the brightly illuminated Art Deco Chrysler Building almost eclipsed by several still-under-construction apartment and office buildings known as “super talls.” Before turning out the light, I noticed on my bedside table The Falconer (Karz-Cohl, 1984) by Donald Knowler a British journalist and avid birdwatcher who set himself the challenge of listing all of the birds that he identified on regular walks in Central Park during a single calendar year.

Throughout the book, which is formatted as a month-by-month diary for the year 1982, Knowler takes the reader with him on numerous exploratory walks beginning on New Year’s Day at the northernmost end of the Park in the Loch. Here he observed “a clear stream that tumbled over two waterfalls between oak, elm, and red maple where once black bear, the indigenous American, and then the European trapper tiptoed in pursuit of deer, the mugger and the wildlife enthusiast tiptoed now.” Here in the heavily wooded North End, as this part of the Park is called, Knowler tells us that he “tramped the stream where blue jays bathe in winter and cottontail rabbits come to drink in the spring, climbing above a waterfall near the west section of the park’s circular drive. A bedraggled gray squirrel shook rain from its back and scampered over the roots of an oak on the far side of the road.” Fast-forward to the last chapter where, with justified pride, Knowler recounts that on his final walk that year, which occurred on December 31, “the red-headed woodpecker, which I had first seen in November, became my one hundred thirty-first bird and would remain my total at the year’s end.”

Knowler borrows his book’s title from the plaque on the sculpture named “The Falconer” that crowns the knoll on the south side of the Park’s 72nd Street drive. The Falconer, however, is a book about humans who call themselves birders as they go on short walks or long hikes with the objective of sighting and listing diverse avian species in various environments throughout the world and has nothing to do with the diurnal bird of prey with long pointed wings and a notched beak that is trained to serve as hunter’s means of seizing game from above. Bestowed by Knowler as an honorific avocational moniker on the person who next to Knowler himself is the principal protagonist in The Falconer, is a passionate and knowledgeable birdwatcher and nature-lover named Lambert Pohner, who was a regular visitor to Central Park from the late 1940s until his death in 1986 at age 59. Himself a passionate birder, Knowler had become acquainted with Lambert in 1982 during his year-long project of compiling a numerically annotated record of the various species of migratory and resident birds he saw on each of the regular walks he took within Central Park.

Notice that in the above sentence I refer to Pohner by his first name. This is so because of my own relationship with this passionately curious and enthusiastically generous Central Park regular who nourished my own Central Park love affair with much appreciated tutorials during our numerous walks together in the Park. More than simply an avid birder, Lambert was a born naturalist, who once remarked to me, “The parks of New York City are my estates, but Central Park is my manor estate.” The breath of his curiosity as he explored every corner of this 830-acre “manor estate” is evident in the album of pen-and-ink drawings with colored wing patterns collectively composing a complete inventory of the butterfly population in Central Park as a gift to me and my husband Ted Rogers on the occasion of our marriage on June 26, 1984.

Two year earlier, in 1982, as I was in the first stage of overseeing the implementation of the Central Park Conservancy’s management and restoration plan, it was Lambert’s friendly generosity of spirit that was responsible for his supporting me when one of my earliest efforts to follow Frederick Law Olmsted’s principle for the opening up prime view lines and vistas within Central Park through judiciously selective acts of removal of certain self-propagated common black cherry trees created a highly publicized furor within the Ramble. The intended result of this commonplace bit of professional forestry practice was to open up a northwestern view line from Bethesda Terrace with the Belvedere as its landmark terminus.

To say the least, I was dumbfounded the day I walked to the site to inspect two sample tree removals by the recently incorporated Conservancy’s arboriculture crew and saw the glaring message carved upon the stump of one: “Betsy Barlow is a Psycho Slut.” The meaning of this slur and the identity of the writer will remain forever unknown, but my status and responsibility as the official administrator of Central Park (my professional title as a member of the New York City’s Park Department’s staff during the administrations of Gordon Davis and, later, Henry Stern) was made clear in the May 3, 1982 New York Times front-page article by the reporter Deirdre Carmody in which I honorably acknowledged management responsibility for arboriculture in Central Park and defended the policy of selective tree removals as necessary to the continuation of one of the key principles of Olmstedian landscape design: the opening up of view lines as scenic corridors within a park and its surroundings.

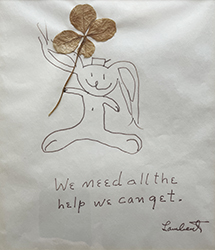

As evidence of Lambert’s obvious neutrality and kindness to me during this time of turmoil, I am inserting here, in the form of the note he sent to me at the end of the year, evidence of the justness of the old saying, “A friend in need, is a friend indeed,” as such was the case during my baptism in the turbulent waters of Central Park-constituency politics.

A sketch of a smiling rabbit holding a pressed four-leaf clover plucked by Lambert Pohner as a gift to Betsy Rogers following an outcry in 1982 by a group of angry birders whom Mr. Pohner had persuaded to end the fight over her decision on behalf of the Central Park Conservancy’s planned removal of a random selection of some self-propagated black cherry trees in the Ramble.

The note, accompanied by Lambert’s ink drawing of a a long-eared, smiling rabbit holding a good-luck emblem in the form of a real picked-and-pressed-and pasted-to-the-page four-leaf clover is dated December 22. 1982, reveals his view of Central Park as an open textbook for amateur naturalists such as Donald Knowler and me while also revealing his character as that of a kindly peacemaker. Naming a married couple, Sheila and Lewis Rosenberg, who for many years ranked among the most devoted Central Park birders with a special passion for the Ramble as a wildlife sanctuary and were part of the opposition who publicly denounced me for my “view lines and vistas” approach to landscape-design, Lambert writes:

“Dear Betsy, Today I received a Christmas card from Lewis and Sheila. I always told them that it is what we do that counts, not what we say. Inside was a sprig of Gracilis from the Big Sky country. My Xmas is made. I cannot think of any gift that could be more fitting. 1982 is a year that began so badly it almost had to end well.

A new grass, a new shrub, and a good and easily identified Tufted Duck on the Rare Bird Alert. A return to Good Will and Amity. Xmas parties and a Grand New Year are sure hard acts to beat. I feel benevolent. Your Love (of the Park) has overcome the obstacles placed in the way. You have taught me a great deal. Others are seeing this and are in the process of reacting to your Love. It is a miracle I knew would happen.”

I now find myself reading Donald Knowler’s account of his walk around the Reservoir on January 3, 1982:

As rain spotted the water the ducks were not to know a cold from the Arctic would reach them in the coming weeks, freezing the surface of the reservoir and forcing them further south. The blue, glossy heads of the male scaups were tucked into the fluffy gray feathers of their backs. The canvasbacks also slept, but some of the ruddy ducks chose to dive, scraping algae and other plant life from the bed of the reservoir.

Yes, I know this to have been the exact scene since I now have in front of me in my own handwriting as penned that very same day, January 3, two years earlier a journal entry that reads as follows:

January 3, 1980

A cold crystalline morning with the wind from the west as Lambert and I walk north along the Reservoir. The frozen ground feels like rough pavement beneath my feet. Lambert, who had offered to escort me to my office today notices that my going-to-work leather pumps are hardly the right walking shoes, but I am warm in my down coat and ready for the “surprise” he has promised. When we reach the pump house at the north side of the Reservoir Lambert solemnly hands me an envelope with my name on it and inside a drawing of a duck with a tuft of feathers growing from the top if its head.

As we scan the flock of ducks bobbing in the water, searching for this relatively inconspicuous bird, I ask Lambert who first discovered this rarity. He replied proudly, “I did. This bird was Central Park’s Christmas present to me. It was like a miracle. I caught a glimpse, just a quick glimpse of its tuft, and at first I thought I might be having an ego trip. Hallucinating. But I knew there was no reason to think that – just walking is my ego trip – so I looked some more. It appeared and then disappeared again. But it was there in the flock. A miracle.

The tufted duck is a European bird, and because it is a rarity in this range it had caused much excitement among Central Park’s birding community. Lambert says that this is the first time he knows of that one has been sighted in the park, commenting, “there was one a few years back in a flock of scaup around Hellgate (i.e. the narrow tidal strait in the East River), concluding, “So it’s reasonable to think that the tufted duck in Central Park belongs to the same family as the scaup and will settle into a flock of these ducks when they stray into North American Atlantic flyway from their breeding grounds in Iceland.”

According to Lambert, birds flying several thousand feet high in the air can see great distances and a duck searching for food may spy a chain of landfalls that carry it progressively farther and farther astray from the normal migratory routes. It will under such circumstances cohabit with a kindred species. As a diving duck like an ordinary scaup, the tufted duck will enjoy the moveable feast of the nutrient-laden currents around Hellgate in the East River, but today this flock in Central Park, along with a number of canvasbacks and goldeneyes, is enjoying the Reservoir as an inland refuge from the cold wind of Long Island Sound, and the ducks will continue here until the Reservoir freezes and they are forced further south. As divers they eat crustaceans and other small aquatic fare that lives in the Reservoir. Because of the prevailing westerly wind today they are sheltering in the northern cove, heads turned one hundred eighty degrees into their protective plumage.

We are systematically scanning the flock for the elusive fugitive when Lambert says, “Look for something resembling a female lesser scaup with a mussed-up hairdo.” I can’t find the distinguishing tuft, but I am absolutely confident that Lambert will. “This bird lives on the brink of reality,” he says, meaning that its presence can easily go undetected, particularly if it will not favor us with a profile that is discernable.

Runners keep loping past us as we creep alongside the Reservoir’s protective chain-link fence looking at flocks of ducks in addition to the scaup. Occasionally, a runner around the Reservoir will stop and inquire about what we are looking at. Lambert warns me to watch out for the serious runners with this cautionary advice, “At a certain point their minds are gone and they are liable to just run you down.”

Then suddenly Lambert calls me. Jumping like a broadly smiling folk dancer doing a jig, he sings out, “There, there!” The duck at which Lambert appears to be pointing is to my eye completely indistinguishable from the rest of the flock of ducks making slow circles in front of us. Keeping his pointing finger and his binoculars at the same angle, he exclaims, There, there!” I am disappointed to have to tell him that I cannot spy the duck with a tuft. “Where is it?” I beg for instructions. Lambert says, “OK. Now fix your binoculars in the direction of the Chrysler building and then come down on the flock.” I do. “Now look at the front of the line. It’s right before us.” Sure enough, there is a small duck with a flyaway topknot. We observe it for several minutes, and I think to myself, “Where else in the world could you take your binoculars down such from such an extraordinary Art Deco pinnacle to focus on such a rare bird!”

Happy in our sighting of the tufted duck, we move on. It is an incredibly beautiful winter day, and I tell Lambert that, although seeing the bird is a great treat, the Park and the Day itself is satisfaction enough. He agrees but believes that this day has been truly blessed by the bird. “It is the fairy princess,” he says, meaning an unexpected delight, a minor but precious miracle.

Lambert’s reverence and passion are inspirational to me and others who know him. He is like a good guru, an exemplar, and my own spiritual impulses are more awake when I am with him. But it is not as some wise elder that Lambert imparts his gifts; rather, it is as a child whose greatness of character lies in an undimmed sense of wonder that prompts him to discover nature’s mysteries each day. Although he would not consider himself to be a writer, he is nevertheless a man of eloquence, a philosopher who speaks to me about his recent warning to a fellow Central Park regular who has just received a paying part-time job after a long stretch of unemployment, not to get lost in the “World of Reality” in order to rest up for the arduous pursuits in the “World of Beauty.” Strict with himself about segregating these two domains, he tells me that he puts on a pedometer every day and does ten miles or more in the World of Beauty before he tells his friends that he has to rest up. Satisfied with this equation of his expenditure of physical energy, he says, “In the World of Reality, meaning a part-time job, I probably only clock a mile on my pedometer.”

We stop at the Swedish Cottage Marionette Theater and drink hot coffee with the puppeteers after which Lambert gives me this compliment: “The way I know you belong in the World of Beauty is because your feet are cold and you fail to take notice” to which I reply with honesty, “That’s because they are numb.”

As we head through the Ramble and circle around the Model Boat Pond en route to my office in the Arsenal, we can see tufts of field garlic poking out of the hard, sere ground and decayed leaves. “Just think, says Lambert, “Spring is only sixty days away!”

_

Still browsing through the hardback account book with lined pages that carry my handwriting of fifty-four years ago, I find myself on March 20,1980, recounting another Lambertian Central Park outing:

I awake at dawn and drowse, enjoying the chirrup of sparrows in the street trees (London Planes, I believe). My head is filled with a list of responsibilities, and I am preparing for work when the phone rings and Lambert offers to share the official arrival of Spring this exact day by walking me to my office. “You have a surprise for me,” I hint eagerly, and he admits that indeed this is so. There will be two surprises in fact.

An hour later I find myself beside Lambert studying the flock of gulls on the Reservoir. “Ooo-ooh,” Lambert cries, “See two red window shades on Central Park West, and let your eyes follow them down to the water and look for a gull without any black wing tips.” I do, the flock, as far as I can tell is made up of herring gulls and a few black-backs, a number of which are immature ones with their confusing unmarked plumage. “There, there,” Lambert points out, “It’s raising its wings.” I watch the gulls gently cruise this way and that, but the plain truth is I just don’t have Lambert’s thoroughly practiced visual discrimination. It is, of course, the minuteness of the differentiations in markings that makes for the thrill of the challenge in bird-watching. “You know,” says Lambert, “sometimes birdwatchers hallucinate. They will actually imagine a rare bird.” At the moment, we are looking for a sub-species of the Iceland gull that is identical to the herring gull except for its smaller size and absence of black wing tips. Lambert is not hallucinating. But, for the life of me, I can’t discern the markings of the bird, although I have it fixed in the scope of my binoculars.

We walk on enjoying the lambent mild morning light. It is the kind of day when one can say decisively, “Ah-ha – spring has come!” Yes, everywhere there are signs of it. The brilliant yellow blossoms of the cornelian cherries (cornus mas) are starting to burst out; the hazelnut catkins have turned a pale green, while the plant shakes and send little drifts of pollen into the air; and what seem like vents in the soil indicate the activity of a myriad of earthworms moving about beneath the surface of the ground.

“Let’s try and beat the little people,” says Lambert. The “little people,” are, as it turns out the schoolchildren whose presence interferes with the ground birds that make their living from the seemingly barren ball fields, not the fantasy folk who, in Lambert’s imagination, sometimes assist in the performance of nature’s miracles. If we are on time today we might see meadow larks; if not, never mind. “What the Lord will provide, he’ll provide,” remarks Lambert philosophically. And “It’s nice to have the juncos singing,” he says as we walk along. He tells me that he has planted some trumpet vine, a climbing shrub with orange or red trumpet-shaped flowers near the Gill in order to attract any hummingbirds that may be visiting the Park next summer.

We don’t find any meadowlarks as Lambert had hoped we would but stood at the south end of the Great Lawn instead and watched the lamp poles being decorated by LeRoy Maxwell and Paul Harnett with fluttering ribbons and plastic flowers symbolic of Spring. The banners that hung from the Arsenal last fall are being fastened to the spire of the Belvedere castle in preparation for the “medieval” celebration of Spring, which Alice Cashman and members of her events staff have organized.

I say good morning to the Central Park maintenance foreman Pete Catapano whose abilities in overseeing park workers deserve a special essay elsewhere, as Lambert and I head up the hill behind the Delacorte Theater and turn toward the Belvedere. One of the workers who is sweeping the path recognizes Lambert and says, “The boss” (meaning Pete) doesn’t want to talk with the public, but, you know, I’m the type that just can’t hold back. I’ve got something I’ve been wanting to give you for a long time. It’s a thing about birds, something I found. I can’t tell one from another, but I think you’ll like it; it’s a list of some sort.” Lambert, who is never at a loss for a gracious reply, “Lists drive me wild. They are like reading a novel.” He then says that he will be passing through this part of the Park frequently now that it is Spring and that when it is no trouble and Pete’s back is turned the workman can slip back to his locker in the Maintenance Yard and fetch his gift.

We then admire a shrub called ninebark; its branches shedding their outer layer in long shreds. Lambert says that it will soon bear lovely long blossoming white umbels. Entering the Ramble, we listen to the sound of a flicker, a vocal rattle followed by a sharp knocking-on-wood cadence. “This is the first day I’ve heard them sing,” Lambert remarks. There are grackles on the ground, which prompts Lambert to instruct me on the relationship between grackles and pine trees. Pointing to some nearby pine trees, he says, “They are a noble bird if they inhabit your grove of pine trees. Otherwise people consider them a nuisance.” We duly note the classical harbinger of spring: a robin and, as we tramp across some catalpa husks, Lambert points out a new wooden birdhouse. “Bill Edgar’s bluebird nesting box,” he says.

The Park is at its most drear moment now in spite of the abundant promise in the swollen buds of sprouting plants, but the ground is muddy and the soil erosion, tire tracks of Parks Department maintenance vehicles, and wearing away of grass have not yet been eradicated by the greening of weeds and vines and wildflowers. The Ramble’s broken drainage system makes the ground so swampy in places that it reminds me of Olmsted’s narration of how he was led through all the boggy spots on his first visit to the Park in 1857 as the newly hired superintendent of its general overall pre-landscape-design clearing operations. It was obvious to him at the time that because of his gentlemanly dress and elite persona he was being put to some kind of test. Today the intricate system of drainage tiles that was installed according to the engineering requirements necessary for the ongoing existence of the water bodies within his and Calvert Vaux’s Greensward Plan are clogged and broken. Therefore, in the Ramble old springs percolate to the surface and take their course across pathways, creating streamlets that eventually flow into the Lake.

We are now in quest of a woodcock, which has been sighted in this part of the Ramble recently. I am feeling a bit impatient to get to work as I remember my list of duties to perform this day. But as long as Lambert is stalking around, intent on flushing it, I remain transfixed and cannot leave. We watch in vain beneath the willows in the “Oven,” the birders’ name for the bedrock-bordered indentation in one of the coves edging the shore of the Lake. Still, I am happy enough without the woodcock as I remember ice skating with my friend Michael Mills into this area, on an unforgettable winter Sunday six weeks ago before continuing over to Ladies Pavilion on the rocky shoreline of the Hernshead and then spinning around in circles many times before we skated back out into the center of the Lake, arms crossed and joined as in the skating scenes of Currier lithographs, before gliding along beneath Bow Bridge and past Bethesda Terrace and on back to the Boathouse.

Suddenly, Lambert motions me eagerly. He has seen the woodcock! I have never doubted his ability to produce such a miracle, and he has never disappointed me. We watch the large stocky bird probing with its long bill in the leaf litter. Its feathers are an artful camouflage, altogether beautiful, and its eyes are set in the top of its head so far back that it must have extraordinary peripheral vision, while the sensory detectors in its bill vibrate about in the mud, allowing it to collect worms and crustaceans without ever seeing what it is eating.

I remark on its curious bobbing motion, a rhythmic heaving back and forth in imitation of the woodcock’s movements. “That’s right,” says Lambert, “see, the rhumba!” as he shuffles his feet this way and that in step with his rhythmic vocal chanting of “one-two; one-two-three,” like a dance-master.

Having rung in Spring with the Woodcock Rhumba, Lambert and I cross Bow Bridge and head toward my office in the Arsenal.

An idea of the administrative work that I was doing in that office and is worth discussing in these pages, which are currently providing the digital document that is preserving for posterity such excerpts from my earlier hand-written journals. More pages from this source will appear in future postings carry information about the birth and growth of the Central Park Conservancy and the changing face of the Park as its rebuilding within the parameters of its original designers’ intent and the preservation of its democratic role as a park for all people moved forward day by day and year by year. That such continues to be the case today under the administration of Betsy Smith is one of the great joys of my life.

For the moment, follow me and Lambert Pohner on a walk in the Park on September 4, 1980:

A mild haze envelopes the Reservoir. A workman in a rowboat along with other workmen from the Water Resources division of the NYC Environmental Protection Department are pruning the volunteer weed growth in the riprap around the edge of the Reservoir: tridens flavens with soft purple panicles, sycamore and maple seedlings, and phragmites sending long rhizomes into the water. “Looking,” says Lambert, “for new lands to conquer.” The man in the rowboat is moving across the water against the towered background of Central Park West toward a drifting loon. “He’s not really working, just looning around,” says Lambert. The loon has been on the Reservoir all summer, a young bird that didn’t make it up to the Adirondacks this year. Now it has been joined by a cormorant.

A large cherry tree on the south end of the Reservoir beside the pump house is loaded with ripe cherries – along with a passel of voracious pigeons. “The warblers do it much nicer,” Lambert informs me that this is the season of the birds’ “bacchanal,” with fermenting fruits galore.

Beside the 86th Street Transverse we inspect a cardinal’s nest in a white pine tree. The baby cardinals have all fledged, and the nest has been abandoned. “Look,” cries Lambert, pointing to a blade of orchard grass; “It’s a rosy maple moth.” I discover that Lambert has for the last year or so been mastering the markings of various butterfly species and compiling a list of all the ones to be found in Central Park. So perfectly camouflaged is the moth that I never would have spotted it, but now we study its dusty rose-beige wings flattened out along the axis of the blade of orchard grass. Then Lambert utters another delighted cry. There is a pearled crescent butterfly on a piece of ragweed. It is lovely to behold, orange with white-dotted wings. Some maple leaves spiral to the ground, which signifies an early fall this year. “Leaf birds,” Lambert calls them.

Beside the 86th Street Transverse we inspect a cardinal’s nest in a white pine tree. The baby cardinals have all fledged, and the nest has been abandoned. “Look,” cries Lambert, pointing to a blade of orchard grass; “It’s a rosy maple moth.” I discover that Lambert has for the last year or so been mastering the markings of various butterfly species and compiling a list of all the ones to be found in Central Park. So perfectly camouflaged is the moth that I never would have spotted it, but now we study its dusty rose-beige wings flattened out along the axis of the blade of orchard grass. Then Lambert utters another delighted cry. There is a pearled crescent butterfly on a piece of ragweed. It is lovely to behold, orange with white-dotted wings. Some maple leaves spiral to the ground, which signifies an early fall this year. “Leaf birds,” Lambert calls them.

We traverse the Great Lawn and then enter the Ramble. For several minutes we study the large clump of wild rice growing along the east side of Bank Rock Cove at the northern end of the western arm of the Lake. Then, turning in the opposite direction, we focus our eyes upon the overhanging branches of a London Plane tree growing at the water’s edge. Lambert says that the green heron that has recently caused a great sensation among Central Park’s regular birders is there because he can see its legs. I can’t for the life of me spot any legs or bird feathers. Pointing to the clump of wild rice growing in the wet soil, Lambert says, “The goldfinches will figure how to work this patch, and then the ducks will come through, and it will provide food for them. We spot a redstart and know that the fall migration has begun.

According to my September 15 entry in my journal for the year 1980, I visited Bank Rock Cove again with Lambert and had the following observations to report:

“Heron Heaven” with Lambert. The Fall migration is apparently slow in gaining momentum this year, but although it is a motionless as a statue, the green heron is clearly visible today. “See. It is in its invisible pose,” says Lambert. A rat is nibbling grass seeds at the water’s edge. “Look at that malevolent eye,” says Lambert, “I’m glad I am not a frog.” Not even herons interest us today, however, for we are in quest of another avian treasure: a Western flycatcher 1,500 miles out of its normal range. We stand on the wooden bridge spanning Bank Rock cove and watch a large viburnum suddenly become all action. “A flock of flycatchers; they travel in families” announces Lambert. Now the birds are darting in and out of the viburnum leaves, and sure enough, Lambert’s “surprise,” the Western flycatcher, is visible and appears to be dancing with excitement. “I am so glad you were with me,” he says as he steers me alongside him as far as the Bethesda Terrace, “in case I need a witness.”

Turning to the next page of my 1980 account book, I find myself penning an entry for September 23rd of that year. It is obvious here that, as eager as I was to be as knowledgeable as the average birder, my real attachment was to my still new job as Central Park administrator and founder of the Central Park Conservancy in implementing the mission statement I had coined for this novel new public-private civic organization: “To make Central Park Clean, Safe, and Beautiful.”

_

As is the case with birding, landscape management on a daily basis begins with the subject of weather, which is evident from the following observation:

The Park is exceedingly dry this year; many dying plants are to be seen. Yesterday we planted shrubs along the 72nd Street Drive. My Wellesley Medieval Art History classmate Phoebe Weil, who is now an expert in bronze sculpture conservation, is helping me launch the Conservancy’s recently recruited crew for this form of maintenance by cleaning the three laughing maidens dancing around three jets of water in the Untermyer Fountain in the Conservatory Garden, a process that begins with a high-pressure shower of miniscule glass beads to break away the corroded surfaces of the sculptures and concludes by their re-patination with a sheer metallic bronze paint.

We held a Latin Jazz concert in the Garden last Sunday which was greatly appreciated by the Puerto Rican neighbors living next door in East Harlem. I took pictures and ate a cuchifrito thoughtfully brought to me by Carlos Ortiz, who is a member of the Park Rangers, a security corps organized by Gordon Davis as a prerogative of his position as Parks Commissioner.

Bill Beinecke has accepted the chairmanship of the Conservancy and, together, we are building a board of directors. Current projects going slowly: the brick company for the Cherry Hill Concourse restoration has stopped production because of a factory problem; Bethesda Fountain plumbing is a mess and expensive to replace, the steel beams in the Belvedere castle’s turret turn out to be eroded, etc., etc.

All of these problems can – and will – be solved. More depressing is the Park Department’s Design-and-Construction Division’s new “landscaping” at the 59th Street Pond, a project that has been in the pipeline since 1974 and is now emerging with all of the heavy-handedness and over-engineering that I deplored when the project was still in its planning stage, but worse because badly executed. Roughly built stone retaining walls, paths wide as boulevards, and concreter curbing everywhere!

The final memorabilia document I have bearing Lambert’s name, but not his talented penmanship, is a hand-out program, which reads:

Memorial Ceremony

for

LAMBERT POHNER

The Ramble, Central Park

October 2, 1986

Henry J. Stern

Commissioner of Parks & Recreation

Elizabeth Barlow Rogers

Central Park Administrator

I cannot now remember how many of the Park’s birding regulars were there nor what was said as we gathered in the center of the Ramble beneath the canopy of the magnificent tupelo tree that gives its name to the meadow in which it stands. I would not have recognized Donald Knowler, whom I think of in a sisterly way as a devout Lambert Pohner devotee like me, for we had then, and still have not yet, met. He was at least there in spirit on this occasion of impromptu reminiscences and must still feel blessed to have had an active kinship with Lambert’s love of Central Park and the cornucopia of nature’s amazing gifts that it spills forth season after season and year after year.

As for me, I was cheered to be standing among some of the members of the New York City chapter of the Audubon Society who greeted me with general amity now that the fracas over the Conservancy’s tree removals in the Ramble in the Spring of 1982 had been put to rest. We were all there as celebrants of the life and passion for nature of one singular man, and his spirit still radiated the beauty of a life lived with the joyful curiosity of an especially gifted child whose unwritten contract with Planet Earth is one of excited exploration.

_

My December 28, 1980 journal entry reads, “New Year’s resolve: to write more regularly in journal. Other resolves: to curb impatience, to leash fantasy and expectation, to manage personal finances more astutely, to become more methodical and businesslike (systematic) in job – but not at the expense of imagination and creativity.”

As I copy this bygone message to myself, I am witnessing the beginning of another new year, this one being 2025, thirty-nine years after Lambert’s memorial celebration in the Central Park Ramble. “What,” I wonder, “is my job now, other than that of a self-propelled literary career with a strong retrospective dimension?” This puts before me task of continuing to search within my records of bygone days the experience of what it was like each step of the way from the time of the Central Park Conservancy’s founding in 1980 until my decision at the end of 1995 to resign from my dual-role employment as the New York City Department of Parks’ first Central Park administrator and the founding president of the Central Park Conservancy with confidence that this unprecedented career nexus of public and private sector governance had the stability and resources for subsequent leaders, as selected by its board, to continue with new creativity to maintain the life of what had been once a novel experiment in public-private partnership governance of an urban public park.

This journal posting and the five previous ones I have made as installments in my comprehensive essay on a Beginner Education in the History, Natural History, and Landscape Design History of Central Park does not complete the picture I am trying to draw. I say this to give my readers the anticipation of my review of another book by Eugene Kinkead, Central Park: The Birth, Decline, and Renewal of a National Treasure (Norton: 1990), my copy of which bears the flattering inscription, “For Betsy Barlow Rogers, the Park’s devoted Administrator, with every good wish for a successful continuance of her regime as renewal proceeds.” Re-reading it now gives me a flush of pride tempered by acknowledgement of a large debt of gratitude to the men and women who proposed the creation of the Park, the designers who conceived its original plan, the workers who built it, the maintenance crews who continue to care for it, and the volunteers who give unstintingly of their time to serve as assistants to the zone gardeners with designated service areas throughout the Park.

Share