September 8th, 2023

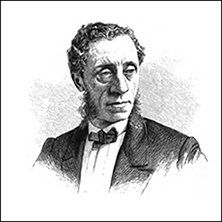

Jacob Wrey Mould: Central Park’s Third Designer

In previous postings of this journal I have discussed how, using its innate geophysical and topographic assets, Central Park’s original designers Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux created a public park in which nature serves as the fundament both literally and aesthetically. In doing so their Greensward plan for Central Park became a seminal example of land art more than a century before this style became a stationery form of long-term performance art.

Olmsted and Vaux’s conception of the park was one of an integrated scene of woods, turf, and water to be explored on foot, horseback, and horse-drawn carriage by means of a grade-separated circulation system that avoided dangerous intersections for different modes of movement throughout the park. The result was wrought- and cast-iron bridges overarching the park’s bridle trail, stone arches carrying pedestrian paths beneath carriage drives, and bridges spanning water bodies at places where crossings were necessary, the most notable being the Bow Bridge, which overarches the lobe of the lake in a gentle curve from the foot of the eastern perimeter of Cherry Hill to the southern entrance to the Ramble.

It was thanks to the genius of Jacob Wrey Mould, an artistically inclined Victorian architect, that the design of Bow Bridge and several other gracefully conceived painterly and sculptural structures made carved stone and decorative color intrinsic features of the park’s design. Although he was sought after as an architect of churches and ornamentally elegant rural homes, including the multi-storied mansion and studio built for the prominent artist Albert Bierstadt overlooking the Hudson River in Irvington, New York, his greatest accomplishment as an architect was achieved in the design of the ornamental features through which he embellished the park’s original Greensward plan. .

It was thanks to the genius of Jacob Wrey Mould, an artistically inclined Victorian architect, that the design of Bow Bridge and several other gracefully conceived painterly and sculptural structures made carved stone and decorative color intrinsic features of the park’s design. Although he was sought after as an architect of churches and ornamentally elegant rural homes, including the multi-storied mansion and studio built for the prominent artist Albert Bierstadt overlooking the Hudson River in Irvington, New York, his greatest accomplishment as an architect was achieved in the design of the ornamental features through which he embellished the park’s original Greensward plan. .

Because Mould became as important a contributor to Central Park’s landscape as Olmsted and Vaux, I wish to go beyond the description in my previous journal entries of Central Park as an original work of land art, which it undoubtedly is, and explore another aspect of its status as a great work of art. This can be defined as its embellishment through the fusion of decorative art with architectural design, an aesthetic approach that is the result of Mould’s joining the original park builders Olmsted and Vaux to form a design trinity. Fortunately, to remedy the overlooked aspect of the park’s appearance after Mould’s hand was combined with theirs, I have next to me on my desk the recently published biography of Mould titled Hell on Color, Sweet on Song: Jacob Wrey Mould and the Artful Beauty of Central Park by Francis Kowsky with Lucille Gordon (Fordham University Press, 2023).

In reading it I was able to explore another layer of what I have previously designated as a a multi-paged architectural presentation palimpsest with the marks on each successive mylar sheet piled together on an architect’s drawing-board, thereby creating an enriched coherent design when the sequential layers of mylar drawings were assembled as a finished design.

Thus was Mould an essential addition to the primary park-design duo, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, thereby making it a trinity of nineteenth-century designers with a picturesque aesthetic who valued the park as a tastefully embellished rus in urbe for city-dwellers.

Notably, it is in Kowsky’s chapter “Embellishing Central Park” where we can learn about how, due to Mould’s participation as a third member of the Greensward plan’s design team, this British architect trained in the aesthetics of Owen Jones, and John Ruskin derived inspiration for the design of the tile ceiling of the arcade below the grand stairway linking the north end of the Mall with the Bethesda Terrace adjacent to the shore of the Lake across from the Ramble.

As the founder of the Central Park Conservancy, I was particularly gratified to read Kowsky’s tribute to my vision:

Angel of the Waters, Bethesda Fountain in Central Park. Photograph courtesy of Sara Cedar Miller.

In the 1970s the park was at the worst it had ever been. Elizabeth Barlow Rogers undertook a campaign to restore the landscape to the days of Olmsted, Vaux, and Mould. Her efforts produced the Central Park Conservancy. “To restore the broken Terrace Fountain with its Angel of Bethesda centerpiece,” Rogers said, “was symbolic of our mission to heal the park. For this reason I chose as our young organization’s logo an image of the fountain.” The Central Park Conservancy’s restoration of Bethesda Fountain through the re-plumbing of its infrastructure of pipes furnishing it with water from the Reservoir and the re-patination of the healing Angel statue’s severely corroded bronze surface was the flagship project of the nascent Central Park Conservancy in the mid-1980s.

This symbolically beneficent landmark consists of a larger and a smaller circular fountain basin, which are visually linked by continuous jets of water, with the upper one surmounted by the eight-foot-tall bronze sculpture by Emma Stebbins of the Angel of the Waters representing the biblical scripture found in the Book of John 5:3,4, which describes an angel from Heaven who “went down at a certain time into the pool at Bethesda and stirred up the water; then whoever stepped in first, after the stirring of the water, was made well of whatever disease he had. ” Appropriately, the bronze sculpture atop the Bethesda Fountain was intended as a symbol of the coming of New York City’s pure water supply with the construction of the Croton Aqueduct in 1842.

Mould also designed the plinth upholding the Angel and oversaw the sculpting of the four cherubs symbolizing the virtues Temperance, Purity, Health, and Peace. The molded rim of the retaining wall of the fountain’s basin, which in warm weather has large water-loving plants floating in it, is almost always occupied by a ring of seated visitors.

Mould also designed the plinth upholding the Angel and oversaw the sculpting of the four cherubs symbolizing the virtues Temperance, Purity, Health, and Peace. The molded rim of the retaining wall of the fountain’s basin, which in warm weather has large water-loving plants floating in it, is almost always occupied by a ring of seated visitors.

On the north side of the terrace surrounding the fountain is an inconspicuous landing for row boats, which on sunny days ply the waters of the Lake and from here can be seen gliding beneath the arc of Bow Bridge, which divides the east and west lobes of the Lake. On the Terrace there are invariably people walking as couples, families, or single spectators enjoying the scene as they gather around the buskers, usually musicians, who make a living from the tips deposited in their open instrument cases.

_

This past Friday, which was a beautiful late-summer day, my husband Ted and I walked south along the path bordering the west edge of the Lake to the north end of the Mall where the underpass of the 72nd Street Drive is accessed by a broad staircase, which carries the visitor into an arcade with three large stone arches opening onto the circular brick terrace surrounding the fountain. On either side the walls of the arcade have blind arches framing decorative geometric patterns reminiscent of the ones found in Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament.

This past Friday, which was a beautiful late-summer day, my husband Ted and I walked south along the path bordering the west edge of the Lake to the north end of the Mall where the underpass of the 72nd Street Drive is accessed by a broad staircase, which carries the visitor into an arcade with three large stone arches opening onto the circular brick terrace surrounding the fountain. On either side the walls of the arcade have blind arches framing decorative geometric patterns reminiscent of the ones found in Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament.

Across the 72nd Street cross-park drive, which forms a roof over the arcade and lower part of the wide stairway descending from the north end of the Mall. On the east and west sides of the arcade are two exterior stairways with ornamentally carved sandstone balustrades and carved panels of sandstone embracing the exterior of the arcade. On both of these Mould has introduced an iconography representing the four seasons. The intertwined vines, leaves, flowers, fruits, and birds that decorate them are a remarkable tribute to the stone carvers who worked under his supervision to create this realistically symbolic representation of year-round nature.

Whenever I walk down either of these sets of stairs I have to stop and look with admiration at these panels of carved seasonal nature. I take special notice of the birds, a few of which have a single line encircling the neck where a smashed-off head was later replaced with a carved sandstone replica. Such repairs as this I observe with pride, for they were commissioned after much searching by the Central Park Conservancy’s restoration team for the quarry that still offers the same kind of sandstone and an experienced sculptor who could carve replacements for the damaged birds’ heads.

This day, as Ted and I stood on the balcony overlooking the Bethesda Terrace next to the 72nd Street Drive admiring the ornamental Four-Seasons staircases and enjoying the scene of happy park visitors gathered on the Bethesda Terrace below, a Conservancy employee named Darren Rogers, whom I remembered from thirty-five years ago, came over and greeted me by name. As always, I was gratified by this kind of spontaneous reunion with a member of the Conservancy’s original field staff, for truly it is the long-term employees like Darren who have saved Central Park, and out of habit I always deflect the compliments that I receive about the park’s transformation, for it is indeed they who have renewed Central Park to its currently uncompromised naturalistic beauty with their ongoing job commitment, craft skills, and daily management duties.

This day, as Ted and I stood on the balcony overlooking the Bethesda Terrace next to the 72nd Street Drive admiring the ornamental Four-Seasons staircases and enjoying the scene of happy park visitors gathered on the Bethesda Terrace below, a Conservancy employee named Darren Rogers, whom I remembered from thirty-five years ago, came over and greeted me by name. As always, I was gratified by this kind of spontaneous reunion with a member of the Conservancy’s original field staff, for truly it is the long-term employees like Darren who have saved Central Park, and out of habit I always deflect the compliments that I receive about the park’s transformation, for it is indeed they who have renewed Central Park to its currently uncompromised naturalistic beauty with their ongoing job commitment, craft skills, and daily management duties.

Looking at the panels of intricately carved reliefs decorating the sides of the pair of stairs descending to the Bethesda Terrace, I recalled their erstwhile saturation with graffiti tags that were almost impossible to remove “Do you remember Clyde, which then became Clyde ‘n’ Janet?” I asked Darren. He too recalled the bold black letters made by spray paint that had once saturated every visible piece of the Terrace’s sandstone and also the difficulty of finding an appropriate chemical remover to expunge the graffiti that defaced not only the walls of the Terrace but also many other stone or brick surfaces throughout the park, including granite sculpture plinths, recreational buildings, comfort stations, stone retaining walls, and some of the larger glacially polished rock outcrops.

I realized that an entirely graffiti-free park nowadays was impossible when I spotted a newly scrawled message on the carved sandstone coping of the west wall embracing the west staircase going down to the Terrace. Before we hugged and said goodbye Darren help dispel my dismay when he told me that Conservancy maintenance workers like him carry graffiti remover in the Conservancy carts they drive from one stop to another and, if possible, they expunge the graffiti tags they discover on the spot.

I realized that an entirely graffiti-free park nowadays was impossible when I spotted a newly scrawled message on the carved sandstone coping of the west wall embracing the west staircase going down to the Terrace. Before we hugged and said goodbye Darren help dispel my dismay when he told me that Conservancy maintenance workers like him carry graffiti remover in the Conservancy carts they drive from one stop to another and, if possible, they expunge the graffiti tags they discover on the spot.

Equal in significance to saving the carved panels ornamenting the Bethesda’s Terrace’s two exterior stairways was the repair of Mould’s suspended tile ceiling of the arcade, which represents one of his most ingenious design derivations from Owen Jones. A large number of the intricately patterned encaustic tiles, which had been made according to Mould’s orders by the Minton pottery firm in Stoke-on-Trent were badly chipped, with many broken altogether and no longer adhering to the steel plates that served to hold the mosaic-like tile layout in place. Fortunately, the Minton firm in England is still in business.

The original granite quarry from which we were able to order large slabs of matching sandstone was still in business, but getting the funding and necessary skill set for our Conservancy restoration crew to fit together the remaining unbroken tiles and new ones matching the originals was a project that took over fifteen years to accomplish. At last we had a stack of square steel plates covered with carefully aligned matching tiles ready to be suspended from the ceiling of the arcade.

After they were fit together and fastened to the steel plates that would be fitted together like a geometric mosaic, which was then suspended from the ceiling. The installation of inconspicuous lighting fixtures on some of the ribs of the steel plates illuminated the tiles’ surfaces, making their decorative patterns legible in the low light of the arcade’s interior.

Mould also desired to have music as an experiential pleasure within the park’s naturalistic landscape. Concurring with him, Olmsted and Vaux originally agreed to his notion of concert music wafting from an inconspicuous stage as visitors made their way through the twists and turns of the circuitous footpaths offering a pleasant meander through the Ramble’s thirty-five acres of woodland. Instead and more practically, the end of Mall’s grand allée of overarching American elm trees leading to the stairs descending to the arcade opening onto the Bethesda Terrace became the site of a small Persian-domed music pavilion of cast iron. The popularity of this concert venue continued after Mould’s charmingly exotic creation was replaced in 1923 by donor Elkan Naumberg with the neoclassically styled bandshell made of painted concrete that has remained a park-events venue up to the present day.

Reading Kowsky, you can experience Mould’s unlimited imagination in ornamenting the park with such features as rustic bird cages, a horse-drinking fountain at Cherry Hill, and flower urns atop each side of the Bow Bridge.

Reading Kowsky, you can experience Mould’s unlimited imagination in ornamenting the park with such features as rustic bird cages, a horse-drinking fountain at Cherry Hill, and flower urns atop each side of the Bow Bridge.

In closing, I wish to say that, if you already appreciate Central Park as a great work of land art, which it is in and of itself, you will also appreciate the layer of Victorian loveliness that Jacob Wrey Mould laid upon it within the confines of the Greensward plan, which continues to govern the Central Park Conservancy’s park restoration aesthetics today. For me, there is another page to add to the top of the park’s layered palimpsest of artistic innateness and artful embellishment, which is the one that examines the use of Central Park as an individual artist’s personal space for the creation of a work of conceptual art. In my next posting, please walk with me through Cristo’s Gates!

Share