February 28th, 2025

The Saviors of Central Park: Part One: David Robinson

Looking back on my life as a landscape-restoration-vision-carrier and overseer for twenty years of the rebuilding of the world’s greatest public park – I recall the time when success in this regard was not a foregone conclusion and one of the board members whom I had recruited to provide legal and fiduciary accountability of the newly incorporated civic organization bearing the name Central Park Conservancy thought I should take lessons from a professional consultant in order to apply corporate management norms to my daily operational leadership. Ted Ryan was the name of the management guru who was hired to coach me, and I grew to consider him a true friend in spite of having felt surprised and chagrinned on the day we met following his preliminary interviews with various members of the cadre of applicants I had assembled as Conservancy staff members when, leaning over my desk and holding a pencil in the air, he said, “They don’t like the way you start off every meeting by saying, ‘I have an idea!’ . . . You think you are sending balloons up in the air, and they see bricks falling down into their wheelbarrows!”

Bang! Of course, listening is an art, and as it turned out, far from being an overweening, opinionated boss, I was the fortunate recipient of highly welcome employee talent, with the result that good ideas about how best to work in concert with the Parks Department’s workforce whose members were focused more on District Council 37 of the Municipal Workers Union’s protection of their rates of compensation keyed to existing job titles than on the site-focused aesthetic and environmental recommendations of the Central Park Conservancy’s management and restoration plan.

Although there were a few bumps in the road in the beginning, in 1998 the Central Park Conservancy was successful in obtaining a contract with New York City that awards annual cash appropriations currently in the amount of $16 million to the Central Park Conservancy, provided that the Conservancy raises a minimum of $16 million from private donors toward the $44 million annual maintenance budget for Central Park.

In spite of the fact that I turned out to be a successful fundraiser, the Central Park Conservancy’s accomplishment in becoming a permanent partner with city government for the purpose of caring for the New York City Parks Department’s crown jewel in perpetuity is due in no small part to simple happenstance. Or call it plain good luck when it came to my hiring of field-crew leaders, a staff member for community and governmental relations, and a professional photographer for documenting landscape restoration projects undertaken with both in-house and outside labor as well as routine activities marking the mission of the Conservancy to make Central Park clean, safe, and beautiful.

Ribbon-cutting celebration following the restoration of one of the Ramble’s rustic shelters in 1983 with Conservancy donor Arthur Ross at Betsy Rogers’s right and Rustic woodworker David Robinson and Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis on her left.

It is for this reason that I am herein beginning my first entry in a series of journal postings that will contain autobiographical portraits written by certain Central Park Conservancy employees from the early days of this not-for-profit organization’s existence. These are the men and women that I now refer to as “saviors,” a term I consider befitting because of the results of their particular gifts with regard to the Central Park’s renaissance in the 1980s and ’90s and their exemplary roles in creating and implementing management strategies that continue to be practiced today.

Before committing yourself to reading my forthcoming series of journal postings consisting of current conversations of reminiscence with those former staff members and enduring friends who are now alumni and alumnae of the Central Park Conservancy, please read the prologue below, which will, I hope, serve as a fitting context within which to place the portraits of the Central Park saviors that I plan to draw with their autobiographical participation in this and future postings.

The Saviors of Central Park: Prologue

When prompted to state the rationale behind Central Park’s landscape-design, I say “a fusion of art and nature.” But this simple phrase, although true, does not account for human agency. Craftsmanship, commitment, education, endurance, and expertise are among the personality traits that were necessary to the achievement of an enterprise of the scope and mission of both Central Park’s nineteenth-century creation and its twentieth-century salvation.

Going back in history for a glimpse of the predecessors of the “saviors” with whom I have a personal familiarity, it is well-worth mentioning the arboricultural and horticultural skills of the great Austrian émigré plantsman Ignatz Anton Pilat, who can be counted along with architect Jacob Wrey Mould as a member of the talented team that collaborated with Fredrick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux on the implementation of their Greensward Plan, the winning entry in the 1857 landscape design competition sponsored by the commissioners appointed by the New York City Board of Aldermen to oversee on an annual basis the creation and ongoing management of New York City’s great naturalistic centerpiece of urban planning. Also, not to be overlooked is Egbert Viele, the Park’s original topographic surveyor and subsequent engineer-in-chief, who assisted in the oversight of the regrading necessary to achieve the realization of the Park’s inherently picturesque romanticism. This focus upon the Park’s scenery was achieved by regrading parts of its surface soil and inproving its fertility for the growth of newly planted trees and shrubs through the importation from New Jersey and Long Island of large quantities of fresh topsoil.

Mention of the “fathers” of Central Park must also include the comptroller Andrew Haswell Green, who served as head of the Central Park Board of Commissioners and exercised fiscal authority over the annual budget for the building and maintaining of the Park as well as the provision of attendants for security and visitor assistance.

_

Kinderberg Children’s Shelter, cxxxx.

Delving deeper into the history of the creation of Central Park, an important design component that is often overlooked in descriptions of its surface infrastructure are the rustic wooden handrails protecting the boundaries of certain planted areas and facilitating the ascent of steep slopes in various parts of the Park. On level ground – typically the sheared-off top of one of the Park’s numerous schist outcrops – the rustic style proved to be a desirable design idiom for a summerhouse, a.k.a. gazebo, with contiguous carved wood benches for shady repose during the heat of summer and overhanging round roofs providing refuge on rainy days. Rustic woodworking also yielded an appropriate design vocabulary for arbors arching over various stretches of the Park’s pedestrian paths.

_

Rustic fence being repaired, Shakespeare Garden.

The aesthetic of rusticity as a form of landscape design can be associated with the Latin term rus in urbe, meaning the resemblance of natural countryside within urban boundaries, which brings us to the subject of rusticity as an optional design idiom resulting in some instances in such features as the rustically carved arms and seat backs providing comfort for bench sitters and carved wooden handrails for facilitating the ascent and descent of steep slopes and occasional stairways by park walkers.

For the Park’s designers, familiarity with architectural expressions of rustic rurality was no doubt furthered by trips to summer resorts with scenic lakeside accommodations and walking trails in the forested landscapes of the nearby Catskill mountains. My own experience in 1984 as a guest at the Mohonk Mountain House, where I celebrated my forty-eighth birthday with my daughter Lisa and son David helped foster an appreciation of the rustic features within Central Park.

To gain an impression of the degree to which Central Park was rusticated by the woodworkers employed during the years of supervision by its designers Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, and Jacob Wrey Mould one can consult the annual reports of the Central Park Commissioners. This is something that David Robinson, who is a master of rustic carpentry with a business of his own today, did.

To put into a historical context the accomplishments of this outstanding Conservancy “alumnus” whom I consider to be one of the Central Park’s prime saviors during the years 1982-1986 when he was a member of David Rosen’s carpentry and masonry repair crew and systematically rebuilding deteriorating structures in the Park, I have copied the handwritten transcription of the annual reports of the Park commissioners from 1865 to 1912 that he gave me, which provides a vivid picture of the role of rustic woodworking as design idiom in the ongoing building of Central Park year by year.

9th Annual Report ending December 1865

9 Rustic Seats constructed seating 100 people

11 Rustic Arbors and Summerhouses seating 225 people

This class of structures is very generally used, the

adaptability of Rustic woodwork to the purpose of the park renders its further use desirable.

10th Annual Report 1866

Ramble shelter:

A Floor added to the summerhouse has been laid with a substance known as metallic lava with the view of testing its capacity of enduring the various atmospheric changes

650 feet of Rustic Arbor constructed

One rustic bridge over the Brook

23 seats of Rustic work 260 linear feet

101 Settees totaling 505 linear feet

11th Annual Report, 1867

Employed for maintenance and construction in Central Park, 1867:

1 (Firm) landscape architects

1 General Foreman

3 foremen of laborers

1 mechanic

186 laborers

1 Painter

18 Carpenters

4 Blacksmiths

32 Stonecutters and Masons

13 Gardeners and Assistants

1 Plumber

Constructed:

2 Arbors 54 feet long, 20 feet wide

610 linear feet of seats

135 small rustic bird Houses

100 linear feet of rustic Fence

16 Tables 4 feet in Diameter

12th Annual Report 1868

Rustic work constructed:

895 linear feet of settees

245 linear feet of Arbor

54 feet of Fencing

2 Summerhouses

16 Tables

2 Bird houses

55 Bird Nests

1 Bee Hive

13th Annual Report 1869

Rustic works constructed:

188 linear feet of Bench

50 linear feet of Arbor

One Bridge 13 feet wide and 35 feet long

2 Bridges 13 feet wide and 14 feet long

Annual Report for 1871

May 30, 1870 Resolved 8 hr workday 8 AM-4 PM

Authorized salaries:

Blacksmith 3.50/day

Carpenter 4.00/day

Mason 4.24/day

Stonecutter 4.24/day

Skilled laborers 2.50/day

Annual Report for 1899

Many rustic shelters, bridges, and fences were repaired and rebuilt. The repairs of all such structures in the Ramble were completed.

Annual Report 1908

Reconstructed following rustic shelters:

Octagon Summerhouse in Ramble south of the Belvedere

Oblong Summerhouse west side of Ramble near women’s cottage

Octagon summerhouse south end Ramble

Umbrella summerhouse south end Ramble overlooking Lake

2 Rustic Arbors 72nd Street and West Drive

2 Rustic Arbors 7th and 8th Ave

Rustic arbor near 59th St. and 7th Avenue

Annual Report 1912

Repairs to rustic umbrella summerhouse in Ramble near Webster statue.

_

Turning now to the present day, meet the team of Central Park Conservancy staff members who dedicate their design and construction skills to restoring existing rustic structures such as the ones catalogued above and creating new ones within a paradigm of historic rusticity. They are, in alphabetic order: Irfan Haider, Assistant Architect; Troy Millard, Project Manager of the Rustic Structures & Chess-and-Checkers House atop the rock outcrop named Kinderberg; Harriet Provine, Project Manager and Architect; and Matt Reiley, Manager of Conservation and Preservation. These Conservancy employees in its restoration design office are currently supervising a large-scale rusticity-revival in the Ramble with the rebuilding of six original summerhouses by outside contractors. They also oversee the work of a field crew, which is carrying the rustic construction ethos into the rest of the park, as is evident in my verbatim copy of a recent posting on the Central Park Conservancy’s website, which reads as follows:

The Conservancy’s dedicated three-person rustic crew – Sam Vargas, Gabe Hernandez, and Rith Hun – continues the rustic tradition, creating original pieces and renovating existing structures. There are currently more than 140 rustic structures in the Park. Staff at the Mohonk Mountain House, a New York resort that features the most extensive and varied collection of American rustic work, trained the Conservancy’s first staff members who worked with rustic structures in the 1980s.

The Conservancy’s present-day rustic crew’s latest project includes a new bench and two bridges – all made with black locust wood – in the Ramble. Designs for these pieces, and any other rustic pieces in the Park, are created by the Conservancy’s Planning, Design, & Construction team. It’s then up to the rustic crew to make them come to life. For the latest bridge, the crew sawed down pieces of wood to create lattices, then drilled them into place. Their final step on any project is sanding the wood. If you spot a light-colored rustic piece in the Park, you’ve likely found a new addition – the wood gets darker over time.

1. Ramble shelter: Inside the Ramble, which Park co-designer Frederick Law Olmsted called a “wild garden,” you’ll find this structure which features its original 19th-century posts.

2. Hallett Nature Sanctuary: The Park’s smallest woodland landscape recently opened to the public for the first time since the 1930s. Its hand-crafted, wooden gate acts as a visual transition to welcome visitors to the sanctuary. Don’t miss the Hallett’s scenic overlook which features rustic railings and benches.

3. Cop Cot: The Park’s largest wooden rustic structure, this shelter is perched atop a large outcrop at Sixth Avenue and 60th Street. The Conservancy renovated it in 2015 and installed two new sets of rustic benches.

4. Ravine overlook: The Conservancy recently completed a major restoration of the Ravine and Loch, which included the addition of several new rustic features – most notably a stunning scenic overlook.

5. Bank Rock Boat Landing and Wagner Cove Landing: In 2016, the Conservancy reconstructed five boat landings to be faithful recreations of landings featured in the Park’s original design. These two boat landings showcase the rustic style and provide beautiful views of the Lake.

Rustic pieces help support the scenic character of the Park’s landscapes, providing increased enjoyment for visitors and creating an atmosphere reminiscent of the Adirondacks, an original intent of the Park’s design. With the help of rustic architecture, visitors can experience nature and a respite from the City while admiring beautiful, handcrafted pieces of history.

_

My book Saving Central Park: A History and Memoir, which was published in 2016, is dedicated to the men and women who built and rebuilt Central Park. In this personal journal entry I now take pride in dedicating the words I am writing here to Betsy Smith, current president and chief executive officer of the Central Park Conservancy, who is drawing on her knowledge of the Park’s rustic design history to preserve its distinctive woodworking craftsmanship within the modus operandi of the current landscape custodians of Central Park..

_

Now, I would like to introduce the man who was, and remains, an exemplar in this regard: David Robinson, whom I consider to have been one of principal saviors of Central Park during the time the Conservancy began the implementation of its management and restoration plan in the early 1980s. David, who was a member of the team headed by David Rosen, which was tasked with carpentry and masonry repairs of broken bridges, walls, stairs, pathway paving curbs, and sundry other elements of the Park’s hardscape. Among these, of course, were the park’s various rustic features.

Following my suggestion that he meet with the creators and caretakers of the rustic architectural structures at Mohonk Mountain House, David honed his already well-developed talent for rustic artistry and began engaging in the kind of woodworking that constituted the prior rustic revival in advance of the one that is currently underway.

By that time, in the early 1980s, the Park’s rustic summerhouses had become overnight encampments for homeless individuals, but this did not create an impediment to their being rebuilt since PEP (Parks Enforcement Patrol) officers routinely routed them in the early morning.

Today I am not surprised that the rebirth of the gazebo as a Central Park feature sparked interest in my longtime friend Lynden Miller, whose own story as a Central Park Savior will be told in a future journal posting in which her genius as an abstract expressionist artist and passion as an anglophile gardener were combined in the restoration of the Conservatory Garden in the North End of the Park. As it happened, for two weeks at the beginning of 1986 Lynden’s creativity was being employed outside of the Park in creating arrangements of plants in the main hall of the Park Avenue Armory to set off the booths of the dealers at the annual Winter Antiques Show, and she succeeded in getting the show’s sponsors to commission David Robinson to build a rustic gazebo as an eye-catching gardenesque feature in the central crossing of the two middle aisles lined with booths showcasing antique furniture and jewelry. Not surprisingly, there were visitors to the antiques show who wished to purchase the gazebo outright or commission the design and construction of a replica for their summer-home garden in the Hamptons. Such was the impetus for David to become an independent businessman and set up the office cum woodworking workshop he christened Natural Edge in Trenton, New Jersey.

_

Betsy and David reminisce in his workshop, October 2024. Photograph by Dan Robinson.

It was a beautiful fall day in 2024 when my son David Barlow, daughter Lisa Barlow, Lisa’s husband Alan Towbin, and I drove down from New York City to spend several hours with David, his wife Abby, and son Daniel, first in the Trenton warehouse building in which Natural Edge is located and then driving through the environs, which include the campus of Princeton University and other sites boasting rustic furniture and structures built on commission by David.

Today, David can look back with satisfaction on continuing to live the of satisfying life of a talented craftsman, and it with great pleasure that I am publishing herein the memoir he graciously wrote at my request.

_

Memoir of a Woodworking Artisan by David Robinson

I call myself a woodworker, working in one of the world’s oldest professions – wood gathering and building. I am a twentieth/twenty-first century rustic woodworker. Carrying on an ageless tradition of building furniture and garden structures with natural logs and tree branches. People in all walks of life remember rustic structures they experienced as a child – a vacation or camp cabin, an arbor or porch swing at a grandparent’s farm, or a rustic seat in a local garden or state park. I am in the business of creating rustic fantasies in wood for a new generation of children’s future memories.

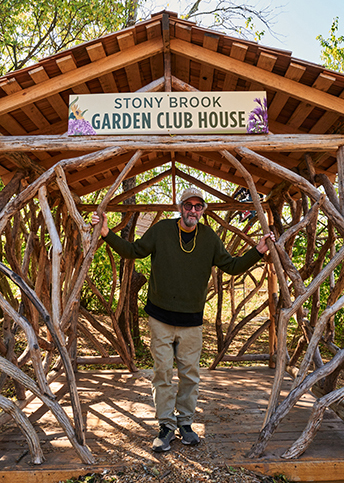

David stands inside a recently completed structure. Photograph by Lisa Barlow.

I build garden follies, hammock houses, bird nesting boxes, tree houses, bridges, benches, beds, tables, fishing cabins, park pavilions, arbors, fencing, railings, gates, and anything else a client asks for. The rustic experience has taken me across much of the eastern United States, making rustic structures from the Rocky Mountains in Colorado to the Rockefeller Center Channel Garden in New York City, and from the Blue Ridge Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, along the Appalachian Trail, through Virginia and Maryland, along the Hudson River Valley and all the way to the Adirondack Mountains in New York State. I’ve worked at amazing estate gardens on Long Island, intimate urban neighborhood gardens in Brooklyn and the South Bronx, and public botanical gardens and nature centers throughout the northeast. At the heart of it all is the rustic work in New York City’s Central Park, where I was first introduced to rustic architecture and furniture.

I have been making things since I can remember. When I was three- or four-years old Mr. White, a skilled carpenter, came to renovate our house. I followed him around all day. He was missing two fingers on one hand. There was the tree house my friends and I built in the woods up at Rattlesnake Hill. The two-inch scar on my left index finger, cut by the wood-handled hatchet when I was 11, is a constant reminder of days gone by and the spirit and enthusiasm of a young boy. When I was a little older, I ran “Robby’s Fix-It Shop” out of the garage where the neighborhood go-carts were repaired because my house was at the bottom of the hill.

When I left New Hampshire for San Francisco in the 1970s, I took the passion to make things with me. While studying art at San Francisco City College and San Francisco State University, I apprenticed myself to Jacques Overhoff, a Dutch sculptor. Jacques had joined forces with two Welsh brothers, Reginald and Peter Locke, an engineer and machinist respectively, to build architectural scale precast concrete and bronze sculptures for public plazas throughout the city. We worked in a waterfront studio on the San Francisco Bay, next to the Bethlehem Steel Shipyard. Two floors above the sculpture studio, a group of smaller live/work loft spaces had been built. I moved into one of the spaces where I could live and have space to work on my own artwork. The space had enormous windows that looked out on the Bethlehem Steel Shipyard. The yard operated around the clock, and I loved looking out the windows, watching tankers being brought into drydock, repaired, and then sent back to the bay, heading towards the Golden Gate Bridge and the Pacific Ocean. My neighbors were painters, sculptors, dancers, writers, designers, papermakers, and more. It was an exciting, inspiring, and creative time for me. I met Abby, an art and architecture student, when she came to work with us at the sculpture shop for a monument restoration in Golden Gate Park. When we graduated, I went with her to New York City, where she was entering a graduate program in Historic Preservation.

In New York, I landed a job with The Parks Department through the Central Park Conservancy. I was the Field Supervisor for the newly formed Central Park Restoration Crew, which was overseen by Construction Manager, David Rosen. I had no idea how much that experience would change the course of my life. I worked in the park for seven years (1980–1987) with a group of hard working, enthusiastic, designers and craftsmen. We restored and rebuilt the naturalistic landscape and architectural features of the park, including rustic stone and wood works. The original Greensward Plan included dozens of magnificent and unique rustic structures. We researched the history of these designs through various architectural archives in New York, where we examined photographs and artists renderings. We took field trips to Mohonk Mountain House and Princeton, NJ to see existing rustic work, first-hand.

The first rustic wood structure we attempted was repairing the only rustic summerhouse still standing in the Ramble. The posts on this structure probably dated back to the nineteenth century. Over my time in the park, we replicated the large summerhouses at the Dene, (Fifth Avenue at 67th Street) and the CopCot (59th Street at 6th Avenue), the arbors at the 72nd Street entrance at Central Park West and many smaller bridges, railings, seating, and arbors. We also restored rustic stone constructions in the park. These included the stonework at “The Point,” a spit of land that juts into the lake near the boathouse, and stone steps in numerous locations throughout the park. Through the research and construction work I did, I developed an appreciation for the fine craftsmanship and design sensibilities of the early rustic builders, led by Anton Gerster in the 1860s. He and his men used only hand tools and their knowledge of wood construction to build the many rustic structures in Central Park.

While working in the park, I noticed a growing public interest in gardening, garden restoration, and natural or rustic design in furniture, architecture, and gardens. With that in mind, I embarked on my own rustic woodworking business in 1987. I named it “Natural Edge.” I will never forget the unbelievable years I spent in Central Park with skilled and brilliant coworkers, whom I am still friends with. Central Park is the most incredible, wild, cultured, democratic, beautiful 840 acres I have ever seen.

David with a load of harvested tree stock. Photograph by Dan Robinson.

Each rustic structure Natural Edge works on is created individually from a “pile” of selected tree stock. My design process begins in the forests, woods, fields, and backyards where I harvest the trees and strip away bark from trunks and branches to have the smooth, but still rustic, forms I use in my projects. There is a constant editing process in my mind as I choose a tree or parts of a tree. I look at the individual components of the tree, visualizing the furniture or architectural feature the branch or tree part can be used for. I look at the limbs, (big, small, curved, fork-shaped, twisted, distorted, straight, thick, or thin) greenery, trunk, burls, goiters, and roots. In addition to the design process, I must keep in mind the practical matters of ecology and transportation. I work with forest managers to be sure wooded properties where I cut are being properly maintained to sustain a healthy forest. Once trees are cut down and branches removed, the logs are dragged out of the forest, by hand and tractor, and loaded into the truck or trailer to be transported back to my shop in Brooklyn. (The shop moved to Trenton, NJ in 1991.) Once in the shop my crew, comprised of one to five workers depending on the job, will cut, chisel, lift, fit and connect the logs with timber screws. We build summerhouses, gazebos, arbors, gates, fencing, furniture, bridges, and more in the shop, take it down, and rebuild it on public and private properties.

I have also given talks about rustic building and run workshops with children, adults, and families. I was introduced to Young Audiences, an arts organization that matches schools with working artists. In my case, I offered a woodworking program that combined art, woodworking and environmental education that was adaptable to all ages. For me, creating objects out of natural materials is magical. I believe the primitive and organic quality of rustic wood structures and furniture is relatable and appealing to children’s sensibilities and imaginations. The process of fastening a few branches together to form a chair or a sculptural creature is exciting. I’m always rewarded when I see a young person’s mind focused on the building process and see their face light up as they discover the magic of creating and the pride it brings.

Photograph by Lisa Barlow.

Like other small businessmen, a rustic builder straddles a variety of jobs. I am part artist, businessman, laborer, farmer, truck driver, and salesperson. I enjoy juggling these tasks and delivering a product that my client will appreciate and enjoy. The thing that inspires me, is the connection between the final piece and the place where it began. The “art” in rustic work is about being in the forest and finding the one branch with just the right curve to fit the back of a bench or the entrance to an arbor. I take that branch from the woods, build a structure, and place it in a garden – back to nature. Over time the piece may begin to appear as if it had grown up on its own in the garden. Then I feel I have done my job.

_

In closing this day’s journal entry, I give a heartfelt thank-you to David Robinson for leading my planned journalistic parade of “The Saviors of Central Park.” Here I must observe that the term “savior” has several connotations, primarily of a religious nature, but my desire, to use the familiar saying “to give credit where credit is due,” is to reach back across the years and share with my readers some of the personal histories of the people whose intellects, physical strength, moral values, and particular skills have perpetuated the ongoing public life of a spiritually uplifting place called Central Park. My gratitude to them for facilitating my desire to honor the spirits of Frederick Law Olmsted and its other creators whose gifts ignited my own labors of love and leadership at the dawn of the existence of the Central Park Conservancy is everlasting.

Finally, I wish express my hearty approbation regarding Central Park’s current saviors, which broadly include members of the Conservancy’s board of directors and women’s committee, and dedicated field operations managers and workers, zone gardeners, and volunteers. and generous financial supporters, who collectively provide ongoing custodianship, daily maintenance, visitor services, and necessary funding to sustain Central Park as an incomparable rus in urbe.

Share