November 19th, 2024

A Beginner’s Education in the History, Natural History and Landscape Design of Central Park: Part Three

“Why did I save all of these books and continue to expand my library with Central Park titles?” I ask myself as I think that by now, after more than a half a century of contact with the park both as a public servant or private citizen and my previous authorship of three books in which Central Park is the principal subject, I would have written my last word about this formidable force in charting the course of my life.

Now, with more leisure time for re-reading books, I can rummage through my library for the two great epic poems by Homer and the perennially always-to-be-read-again novels of Leo Tolstoy and George Eliot plus works by other authors writing before the dawning-of-the-third millennium, especially ones who have written about my ardently adopted home New York City (thank you, Robert Caro, for The Power Broker in 1974). As I periodically browse through the titles on the two shelves dedicated exclusively to books on the subject of Central Park, I find the reading of any one of these appealing, no matter whether the publication date is distant or recent. With the discovery of a trove of such books in my library I have turned my current series of entries in this online journal into a sequence of “reviews” of certain park visitor-oriented twentieth-century books in which I call attention to titles that, taken together, constitute a bibliography of instructive on-the-ground-guidebooks for readers who wish to be, or perhaps already are, aficionados of Central Park.

As an aficionado myself ever since I took up residence in New York City sixty years ago, I have unconsciously been the cartographer of a mental three-dimensional way-finding map of Central Park, which is now imprinted on my brain, meaning that I can walk almost anywhere within the park’s boundaries with a clear sense of direction while occasionally enjoying a curiously pleasant sense of disorientation in the park’s two heavily forested areas: the Ramble and the North End.

When someone asks me to name my favorite part of the park, I am tempted to make my answer one or the other of these two sylvan park landscapes, but from the holistic perspective of the park’s overall terrain I have another reply. Summoning to mind the topographically familiar map that multiple memories of past walks in the park have imprinted on my brain, I find a host of images denoting the park’s prominent bedrock outcrops and various recreational destinations constituting important features within the overall scenic panoply of gently sloping hills and valleys, grassy lawns and meadows, and naturalistic water bodies, including three ponds, a rowboat lake, two pools, and two perennially flowing streams, all of which are fed by underground pipes that release water tapped from the Croton Reservoir.

At the time of the park’s construction, this stone-walled, rectangle-shaped reservoir at the foot of Vista Rock, site of the Belvedere, was designated for removal, and the curvilinear-shaped New Reservoir, (the one we know today as the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir in memory of the famous former First Lady whose regular fitness regime included routine jogging on the one and one-half -mile track surrounding it) was being constructed within the boundaries provided by the East and West Drives and the 86th Street and 96th Street Transverse Roads.

_

Both the Ramble, with its ever-flowing artificial stream known as the The Gill emptying into the Lake, and the North End, with the watercourse named The Loch (originally known as Montayne’s Rivulet), running the length of the gorge of the steep-sided forested Ravine before reaching its mouth on the western shore of the Harlem Meer are evidence of the successful hydraulic engineering necessary for the implementation of Olmsted and Vaux’s 1857 blueprint for a park created in the picturesque style of landscape design conceived as a fusion of art and nature with a premium put upon scenic view lines.

Yet it is to another form of engineering infrastructure that I wish to assign my vote of pan-park favoritism: Central Park’s visitor circulation system for moving into, across, and throughout its 830 acres seamlessly via varied modes of locomotion. To justify a proposition that posits infrastructure as one’s favorite place within the park one has to understand the holistic nature of the landscape design plan to which Olmsted and Vaux gave the name Greensward, hereby calling attention to the relationship between the visitor in transit and the natural and naturalistically vegetated grounds throughout the Park as sketched in printer’s ink by lines weaving in and out of spaces with graphic symbols denoting lawns and meadows, skirting the embankments of proposed bodies of water, passing alongside stands of trees and patches of soil sufficiently friable to be planted with shrubs or flowers, and leading to the north-south axially linked spaces that constitute the lively beating heart of the park as embodied by the Mall with its overarching elm tree branches leading to a wide stairway beneath the 72nd Street Drive, therewith bringing the visitor into the Arcade opening out upon the Bethesda Terrace with its eye-catching, bronze angel seemingly descending from Heaven on outstretched wings and alighting atop the fountain erected as a symbol of New York City’s pubic health victory in 1842 through the engineering of the Croton Aqueduct. From this point the central axis of the Park’s design penetrates the boat landing adjacent to the Lake and continues as a view line running through the Point, as this peninsular piece of the Ramble’s shoreline is called.

Jacob Wrey Mould, architect (1825–1886).

To fully appreciate the architectural talent and design ingenuity that this axial flow of connected spaces embodies it is necessary to pay homage not only to Calvert Vaux, Central Park’s primary trained architect, but also to the associate architect Jacob Wrey Mould, whose artistic genius is abundantly evident in the design and carving of the Arcade’s exterior limestone side panels flanking the pair of stairways leading from the 72nd Street Drive’s carriage drop-off platform overlooking the Bethesda Terrace.

_

A Description of the New York Central Park, 1869.

The result of the premium put on park visitors’ enjoyment of Central Park and the concomitant desire for safety within its web of gracefully interwoven pedestrian paths, vehicular drives, bridle trail, and four transverse roads sunken below grade in order to permit traffic to go to and from opposite sides of the park without harming its scenic surface and the people enjoying it, is, yes, my favorite part of Central Park. Fortunately, one of the rediscovered treasures in my trove of vintage books about Central Park is A Description of the New York Central Park (author unknown), which was published in 1869 by F. J. Huntington and Co., 459 Broome Street, New York. Turning open its gold-embossed green leather cover, I fortuitously found an invaluable source for visualizing the park-in-construction during the previous decade. Here I became aware of the fact that Olmsted and Vaux had submitted their design competition entry titled Greensward to Central Park’s Board of Commissioners in the form of a graphic rendering of their plan accompanied by an explanatory pamphlet describing the Park’s main features and the general principles that had guided them in their proposed design. Excerpts of the contents of this pamphlet as quoted after an interval of eleven years between the beginning of the construction of Central Park in 1858 and the publication in 1869 of A Description of the New York Central Park, which I now hold in my hands, provide an in-depth understanding on the part of its authors of what the public needed in a Park of this character and how the needs had been met with regard to visitors’ access to its various scenic and recreational features. In the author’s words:

Central Park was originally planned with an intelligence and foresight that made nothing necessary but to develop the design, and ten years’ use of the Park by the public has sufficiently proved its excellence.

Here a footnote contains the information that 2,998,770 pedestrians, 84,994 equestrians, and 1,381,697 vehicles visited the park in 1867. For the sake of comparison, today Central Park has an average of 45 million park visitors annually; however, this electronically calculated statistic is compiled without information regarding modes of transportation for each park visitor as was the case in the early days of the park when park stewards were assigned to count the number of entrants at each gate. The results confirm this observation by the author of A Description of the New York Central Park:

“The whole Park may be enjoyed by any one, whether in his carriage, on horseback, or on foot; and, though ingenuity always reaches its end at the least expense, yet no necessary expense has been spared to carry out this admirable part of the Park system as perfectly as possible. The drives in the Park vary in width, the widest being sixty feet, and the narrowest forty-five; they are followed in their whole length by walks for pedestrians, but there are a great number of these walks that avoid the carriage-road altogether. The bridle-path is twenty-five feet wide, and, in the southern half of the Park, runs a course quite independent of the drive, but in the northern half, the equestrian has the choice, at present, by turning into the drive after passing the old Reservoir and leaving it again after making the circuit of that portion, or lf shortening his run by rounding the Reservoir, and so home. Meanwhile children, pedestrians, and old or young who come with a book, with knitting, or merely to sit and look on the scene, have, free from interruption either by carriage or horsemen, the Mall, the Terrace, the Ramble, the many picturesque and comfortable summer-houses, and the border walk about the inland sea of the new Reservoir.”

Immediately on entering the southeastern gateway – Fifth Avenue and Fifty-ninth Street – we see on our left hand an irregular piece of water and banks of considerable steepness. This is called “The Pond.” It is about five acres in extent, and like all the water-pieces in the Park, is largely artificial, advantage being taken of the natural drainage of the ground. On the western side the banks project boldly into the water, thus giving it a sort of crescent shape and, by dividing it into two parts, adding greatly to its variety. The banks are quite picturesque; here, a bold bluff on the eastern side answers rocks on the west; here a broad grassy slope descends to the very edge of the water, and on the southern side a sandy beach enables the children to watch the ducks and swans. In the skating season this Pond makes a capital chapel-of-ease to the larger Terrace Lake, and hundreds of skaters stop here at the entrance to the Park in preference to taking the additional walk and joining the larger crowd. As we pass the Pond we see the Arsenal on our right, a large, and by no means handsome building, formerly owned by the State, but purchased in 1856 for the sum of $275,000. This purchase included, of course, the ground on which the Arsenal stands, and it was shortly afterward taken possession of by the Commissioners and used for various purposes. The lower stories served for lumber rooms, and in the upper part the large staff of architects and engineers’ draftsmen found rough-looking, but, on the whole, very pleasant quarters. . . . All of the building, as well as all of the work of every kind that has been done in the Park, is of so solid and excellent a sort, that it must be a perpetual annoyance to the Commissioners to have such a flimsy, make-believe structure at this on their hands. . . . Of late, the Arsenal building has been used as a place of deposit for the somewhat incongruous “gifts” that are made to the Park every year. . . . In the second story are a number of stuffed animals, and on the ground-floor a small but interesting collection of living ones. There are also cages containing eagles, foxes, prairie-dogs, and bears, outside the building, but it is hoped that before long sufficient progress will have been made with the grounds of the Zoological Garden – on the western side of the Eighth Avenue, between 77th and 81st streets – to allow of all the animals belonging to the Park being removed to quarters especially designed for them, suited to their comfort and well-being.

Here, as an aside, I would like to say that for the five years during which I was director of the Central Park Task Force and subsequent fifteen during which I served as the founding president of the Central Park Conservancy, I occupied an office in the Arsenal, a fact that triggers a twinge of nostalgia whenever a see the building from the window of a cab as I pass its entrance opposite the corner of Fifth Avenue and 64th Street. During most of those fifteen years I was familiar with the zoo located at the rear of the building, which had been built under the direction of Parks Commissioner Robert Moses in the mid-1930s on the site where animals in cages were formerly displayed, and I was present at the conference room table when Commissioner Gordon Davis signed the contract in 1988 with the Wildlife Conservation Society, the not-for-profit organization previously known as the New York Zoological Society, to place under its aegis the management of the zoo and later transform the original story-book-themed Children’s Zoo located to the north of the main zoo into a facility that now presents itself as “Home to sheep, goats, zebu, and more, plus plenty of opportunities for young visitors to crawl, jump, climb, and pretend to be animals, the Children’s Zoo always brings out the child in everyone.

_

Reader, as we continue our walk in the company of the author of A Description of the New York Central Park, vicariously feel yourself to be traversing Central Park’s landscape topography and taking note of Greensward plan’s artfully realized design components. Imagine, too, the early maintenance standards upheld by the Central Park board of commissioners and the park visitors’ uses of the newly revealed landscape during the early years of its existence as a world-famous, highly praised public space.

Here I would like to reintroduce into this quotation-filled narrative the architectural historian Henry Hope Reed whose Central Park: A History and a Guide was the subject my first posting in this series of book reviews in which I share the educational validity of the information found in a number of the vintage volumes that still occupy a place on a shelf in my library.

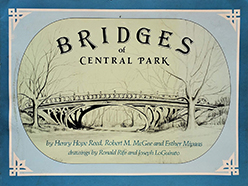

Returning now to my early Central Park teacher Henry Hope Reed, I have on my shelf next to his 1967 Central Park: A History and Guide, his book titled Bridges of Central Park, co-authored with Robert M. McGee and Esther Mipaas, with drawings by Ronald Rife and Joseph LoGuirato, which was published in 1990 by the Greensward Foundation.

Returning now to my early Central Park teacher Henry Hope Reed, I have on my shelf next to his 1967 Central Park: A History and Guide, his book titled Bridges of Central Park, co-authored with Robert M. McGee and Esther Mipaas, with drawings by Ronald Rife and Joseph LoGuirato, which was published in 1990 by the Greensward Foundation.

_

To serve as background for Reed’s art-historical consideration of the ornamental architectural structures found within the park’s interwoven circulation system one must take into account the genius of Olmsted and Vaux’s Greensward plan whereby the park’s landscape which is approached from the perspective of the visitor regarding a series of scenic settings via the grade-separation of different modes of mobility. To achieve this objective, it was necessary to give continuity to pedestrian pathways by tunneling them beneath the East and West Drives and elevating them via cast-iron bridges over the bridle trail. Thus, the park’s designers were able to achieve a hazard-free means for visitors employing three interwoven modes locomotion – foot, carriage, and horseback – to safely enjoy the park.

Bow Bridge, Central Park.

To appreciate the designers’ success in this regard, slowly turn the pages of Bridges of Central Park and, as you move in your imagination along the bridle trail through an archway tunneling beneath one of the park’s vehicular drives or cross it via a bridge carrying a pedestrian pathway above ground level, take notice of the carved stone and cast iron artistry that give you a growing appreciation of the talents of Calvert Vaux and his fellow British-born architect and collaborator Jacob Wrey Mould, whose ornamental design-detailing distinguishes much of the infrastructure of the park’s circulation system, including its carved-stone arches and cast-iron bridges.

In the process of understanding the park as a masterpiece of scenic navigation, walk along the path leading from Belvedere Terrace alongside the foot of Cherry Hill to the pathway that carries you into the depths of the Ramble, which must be accessed by spanning the water where the two wide outstretched arms that constitute the Lake merge within the grasp of the park’s most elegant bridge. Built in 1859–1860, Bow Bridge is described by Reed as “a 142-foot balustrade and wood walkway with ornamental interlacing cast iron railing, piercing with Gothic cinquefoils, mixing details that are essentially classical Greek along with foliated ornament in the more lavish taste of the Renaissance.”

_

Because of the imperative of having a wide horizontal page format to accommodate the necessarily broad dimensions of its illustrations, this excellent guidebook will probably need to be placed in a tote bag when you take it along for reference on a walk in Central Park. This is not something to worry about since the weight of a well-designed 95-page, nine-inch by 12-inch paper-back publication is light, and the text is as instructive as would be the case in the straightforward delivery of a PowerPoint slide lecture by a good art-and-architecture history professor.

The fact that Central Park was intended to be a democratic metropolitan amenity accessible to people of all ages, genders, ethnicities, and occupations is evident from the premium put on the design of its interior circulation system. Advocacy of the ongoing refinements of the creation of such a park continued to be pushed forward by civic-minded New Yorkers and the Park’s Board of Commissioners as will become evident in my next journal posting in which I will review the contents of another vintage Central Park book that I discovered during another inspection of my library shelves. Simply titled The Central Park, it was written, compiled, and edited by The Central Park Association, a distant progenitor of the citizens’ organization that now functions under the name “New Yorkers for Parks.”

Share